Epidemiology

Etiology

Pathophysiology

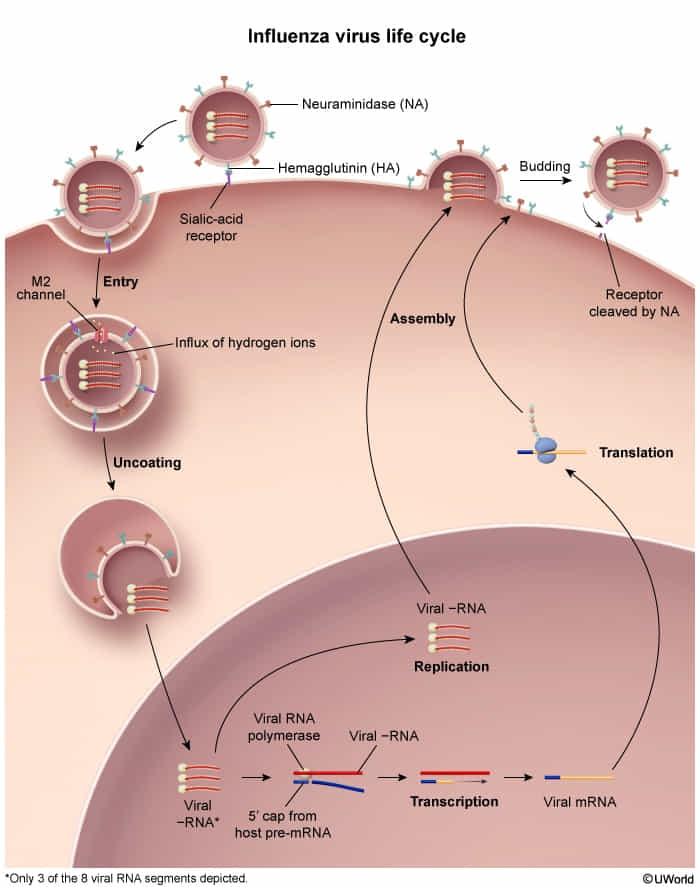

- Replication cycle

- Influenza viruses bind to the respiratory tract epithelium.

- Viral hemagglutinin (H) binds sialic acid residues (neuraminic acid derivatives) on the host cell membrane → virus fusion with the membrane → entry into the cell

- The virus replicates in the nucleus of the cell.

- The new virus particles travel to the cell membrane → formation of a membrane bud around the virus particles (budding).

- Viral neuraminidase (N) cleaves the neuraminic acid → virions exit the cell.

- Host cell dies → cellular breakdown triggers a strong immune response

- Subtypes are differentiated by cell surface antigens hemagglutinin and neuraminidase (e.g., H1N1 is “swine flu”)

- Hemagglutinin (H): promotes viral entry by binding to sialic acid residues

- Neuraminidase (N): promotes the release of virion progeny from host cells by cleaving terminal sialic acid residues

- Genetic mutations

- Antigenic shift

- Two subtypes of viruses (e.g., human and swine influenza) infect the same cell and exchange genetic segments (reassortment) to create new subtypes (e.g., H3N1 → H2N1).

- Causes pandemics

- Antigenic drift

- Minor changes in antigenic structure (hemagglutinin and/or neuraminidase) via random point mutation

- Causes epidemics (limited to a specific population or region)

- Antigenic shift

Clinical features

Complications

Secondary bacterial bronchitis and pneumonia

- Etiology: Common causative pathogens include S. pneumoniae, S. aureus (including MRSA), S. pyogenes, and H. influenzae.

- Pathophysiology

- Influenza virus attacks the tracheobronchial epithelium and results in decreased cell size and a loss of cilia, which promotes bacterial colonization.

- The influenza surface protein neuraminidase also cleaves sialic acid off host glycoproteins, leading to an increased amount of free sugar in the respiratory tract, which fosters bacterial growth.

- Clinical features

- Development of a purulent, productive cough ∼ 4–14 days after an initial period of improvement

- Recurrent fever

- Symptoms similar to community-acquired pneumonia

Diagnostics

Treatment

Prevention

Inactivated versions of the influenza vaccine stimulate the formation of neutralizing antibodies against the hemagglutinin antigen of included strains. Subsequent exposure to a strain of influenza included in the vaccine will not result in infection because the antibodies bind to hemagglutinin, thereby preventing hemagglutinin from attaching to the sialic acid receptor on host respiratory epithelial cells (preventing viral entry).